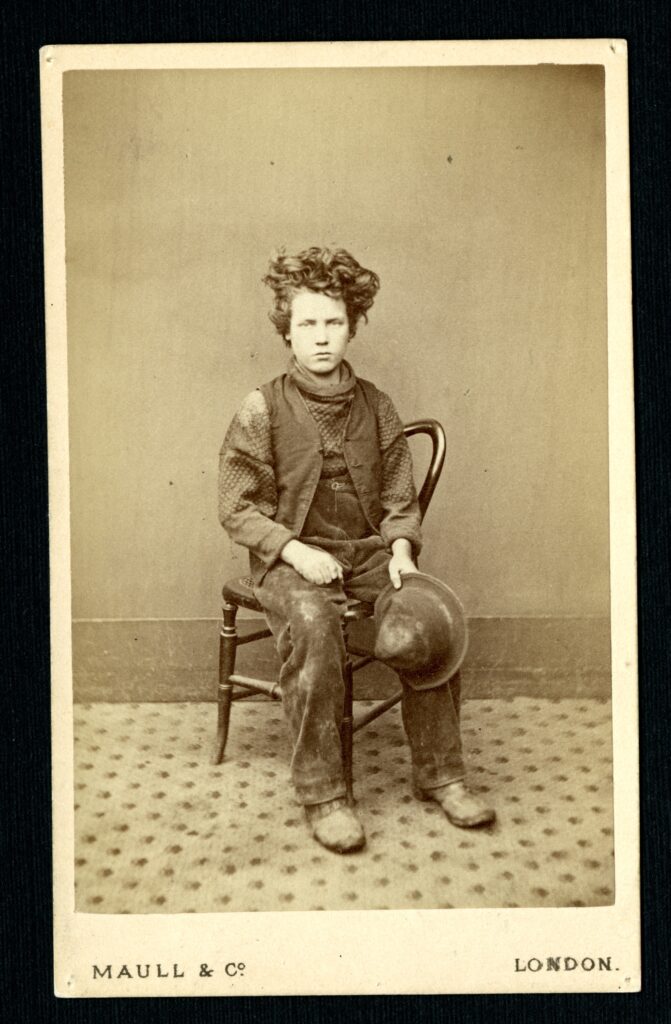

Imagine, at the age of ten, leaving urban Liverpool bound for a life of farm work in Canada, accompanied, not by your parents, but only by a chaperone and a bevy of other children. There is no way to generalize the experience of children in Canada’s Home Children program, which brought upwards of 100,000 children to Canada between 1870 and 1939, with more that two-thirds of children housed with farming families in Ontario. These children were caught at the centre of complex global political, economic, and social forces that shaped the policies and programs that changed their lives (Parker, xii). This site was created by students in DCN2100 and CMN3300, as part of the major in Communication and the minor in Digital Cultures at the University of Ottawa. Students in the course learned to query Wikidata, create visualizations, clean thousands of data records, call up archival material from Library and Archives Canada, and digitize primary source material, all in the service of generating new knowledge about Canada’s Home Children program and sharing it through public humanities scholarship.

The students’ projects give readers the superpower of the Humanities: the ability to understand the current moment, through a nuanced, evidence-backed outline of how we got here. While the recent news of Manitoba’s withholding of $334 million of federal funds for children in foster care, compensation for discriminatory under funding of child welfare, or the link between Canada’s foster care structure and later homelessness has rightly shocked many Canadians, this site will help readers understand that these individual instances of under funding and lack of support for children are not anomalous, but rather are part of a long history of the status of poor children in Canada.

Canada’s Home Children program was shaped by both push and pull forces. A number of factors contributed to child poverty in England, including the economic crises in 1866 and 1871; low sex-differentiated wages; lack of access to birth control; no legal requirement before 1876 for support in the case of desertion or the end of a marriage; and the new evangelical social reforms of the second half of the nineteenth century (Thane 33; D’Arcy; Parker 6, 8). Few Home Children were orphans. The head of one sending organization, John Middlemore, describes a gathering in 1882 in which parents could “meet their children once again, and … bid them a life-long farewell [with] mothers and children…meeting for the last time on earth [providing a scene that] was as pathetic as life could present” (qtd in Parker 32).

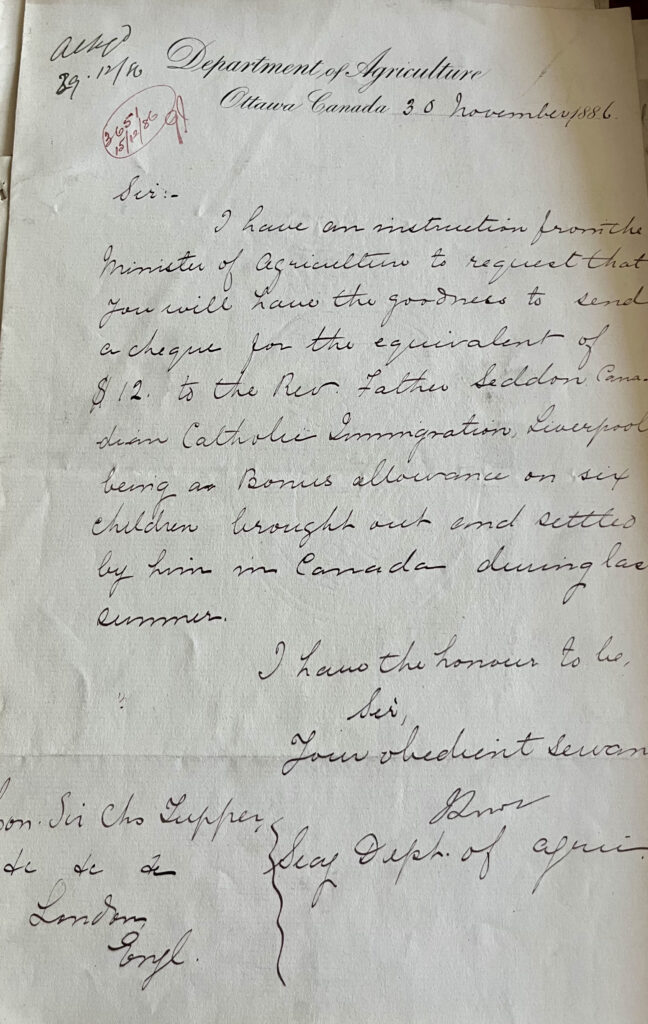

On the Canadian side, the Home Children program was in many ways was a colonial scheme to make up for labour short falls. The program was organized through the Department of Agriculture. Met with class-based hostility, most of the children were not adopted into receiving families, but instead worked as indentured servants, with scant wages held in trust if they survived to the age of 18 or 21 (Corbett; Doyle 11). There were a number of sending and settlement organization who worked with the Canadian government to acquire and transport children, including the Barnardo Homes, Fegan Homes, Roman Catholic charities, Middlemore Homes, and Qaurriers Homes (Neff). The fitness of these organizations for the task varied, for example, in 1873 John Middlemore “admitted… he had made no prior arrangements for the reception or placement [of the 29 boys he had brought from Birmingham] he …’did not know what to do with my children when I arrived’” (qtd in Parker 31). According to one contemporary report “neither in Niagara nor in Knowlton or Belleville, is there any suitable provision for the reception and employment of children” and “the structural deficiencies..noticed at Niagara are still more striking both at Knowlton and Belleville” even if the children were well fed (Doyle 8). Oral testimony accounts of surviving home children’s experiences corroborate the allusions to forced labour and abuse found in primary source documents (British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa). The Government of Canada empowered itself to run this program through several acts, which you can read more about in the Middlemore and Barnardo Timeline.

Record keeping about Home Children varied between charitable organizations. The DCN2100 students worked with Library and Archives Canada data about the children, including spreadsheets with records about the birth places, crossing dates, receiving cities, and occasionally the provenance of individual children. To see a data-backed visualization that attempts to represent the sheer number of children settled in Canada, interleaved with individual accounts of children who might otherwise be reduced to mere data points see Migration Data Visualization. These visualizations are augmented by account of the sending organizations, their founders, and the contexts that enabled this mass migration, in Middlemore and Barnardo Timeline and the Liverpool Catholic Children’s Protection Society.

Several DCN2100 and CMN3300 groups worked on public history projects to explain the effects of the Home Children program to non-academic audiences. For a walking tour of places in Ottawa relevant to home children, and more research material, see the Ottawa Walking Tour Zine and its subpage. The site also features a replica trunk to offer viewers a way of understanding what each child would likely have had to hand. The Colouring Book features a colouring book, introducing the home children program to twenty-first century children. Finally, the Cecil Bennett and Claude Nunney video offers an overview of the lives of two former Home Children who served in the First World War.

As part of the course, the students visited Library and Archives Canada, where they learned how to call up and access archival material. The class digitized primary source material related to emigration and home children in Canada, much of which has only been seen by a handful of Canadians. Thanks to LAC’s DigiLab program, these documents will be made available online for use by researchers across Canada. We relied heavily on the work of the community research group, Home Children Canada’s links into the relevant material in the Canadian Research Knowledge Network‘s Canadiana and Héritage collections. We would like to thank Melanie Brown, Marie Blake, Chloé Bourbonnais, Margaret Couper, and Julia Barkhouse for their support. We will always be grateful to Dr. Bridget Moynihan, who arranged student orientation at LAC as well material access, DigiLab access, and digitization finalization for DCN2100, CMN3300, and DCN1500. Thank you Bridget.

We are also indebted to Dr. Jada Watson, coordinator of the Minor in Digital Cultures at the University of Ottawa. If you would you like to have the archival research, digitization, data analysis, mapping and visualization skills you see here check out the Minor in Digital Cultures and DH at uOttawa.

Constance Crompton

Canada Research Chair, Digital Humanities

Professeure agrégée | Associate Professor

Département de communication | Department of Communication

Université d’Ottawa | University of Ottawa

Works Cited

British Isles Family History Society of Greater Ottawa. British Home Children: Their Stories. Global Heritage Press, 2010.

Corbett, Gail H. Nation Builders: Barnardo Children in Canada. Dundurn Press, 2002.

D’Arcy, F. “The Malthusian League and the Resistance to Birth Control Propaganda in Late Victorian Britain.” Population Studies, vol. 31, no. 3, 1977, pp. 429–48. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2173367.

Doyle, Andrew, fl., et al. Pauper Children (Canada): Return to an Order of the Honourable the House of Commons, Dated 8 February 1875, for, Copy of a Report to the Right Honourable the President of the Local Government Board, by Andrew Doyle, Esquire, Local Government Inspector, as to the Emigration of Pauper Children to Canada. s.n., 1875.

Neff, Charlotte. “Government Approaches to Child Neglect and Mistreatment in Nineteenth-Century Ontario.” Histoire Sociale / Social History, vol. 41, no. 81, 2008, pp. 165–214.

Parker, R. A. Uprooted: The Shipment of Poor Children to Canada, 1867-1917. UBC Press.

Thane, Pat. “Women and the Poor Law in Victorian and Edwardian England.” History Workshop, no. 6, 1978, pp. 29–51.